Traditional arts and crafts suffered greatly during Afghanistan’s long years of civil conflict, but over the last decade, the country has seen a renaissance of traditional art forms and the launch of a brand-new generation of artisans. One group spearheading this remarkable revival is the nonprofit, nongovernmental organization Turquoise Mountain, an international association founded in 2006 that is dedicated to revitalizing historic areas in Afghanistan and to spurring the development and growth of the Afghan arts and crafts industry.

Traditional arts and crafts suffered greatly during Afghanistan’s long years of civil conflict, but over the last decade, the country has seen a renaissance of traditional art forms and the launch of a brand-new generation of artisans. One group spearheading this remarkable revival is the nonprofit, nongovernmental organization Turquoise Mountain, an international association founded in 2006 that is dedicated to revitalizing historic areas in Afghanistan and to spurring the development and growth of the Afghan arts and crafts industry.

One of Turquoise Mountain’s most important initiatives is the Turquoise Mountain Institute. As the premier arts vocational training institution in Afghanistan, the Institute is where the country’s future master artisans get their start. Around 15 students are accepted every year via a highly competitive application process, and successful candidates then receive three years of intensive training in their particular craft from some of the world’s most distinguished artisans (both Afghan and international faculty teach at the Institute).

In addition to offering world-class training in disciplines like woodworking, ceramics, and jewelry-making and gem-cutting, the Institute serves as the home of the Alwaleed Philanthropies School of Calligraphy and Miniature Painting. Calligraphy is a highly revered art form throughout Afghanistan and the rest of the Islamic world, and it has a rich and captivating history that few Westerners are familiar with. Read on for some fascinating facts about the beautiful art of Islamic calligraphy.

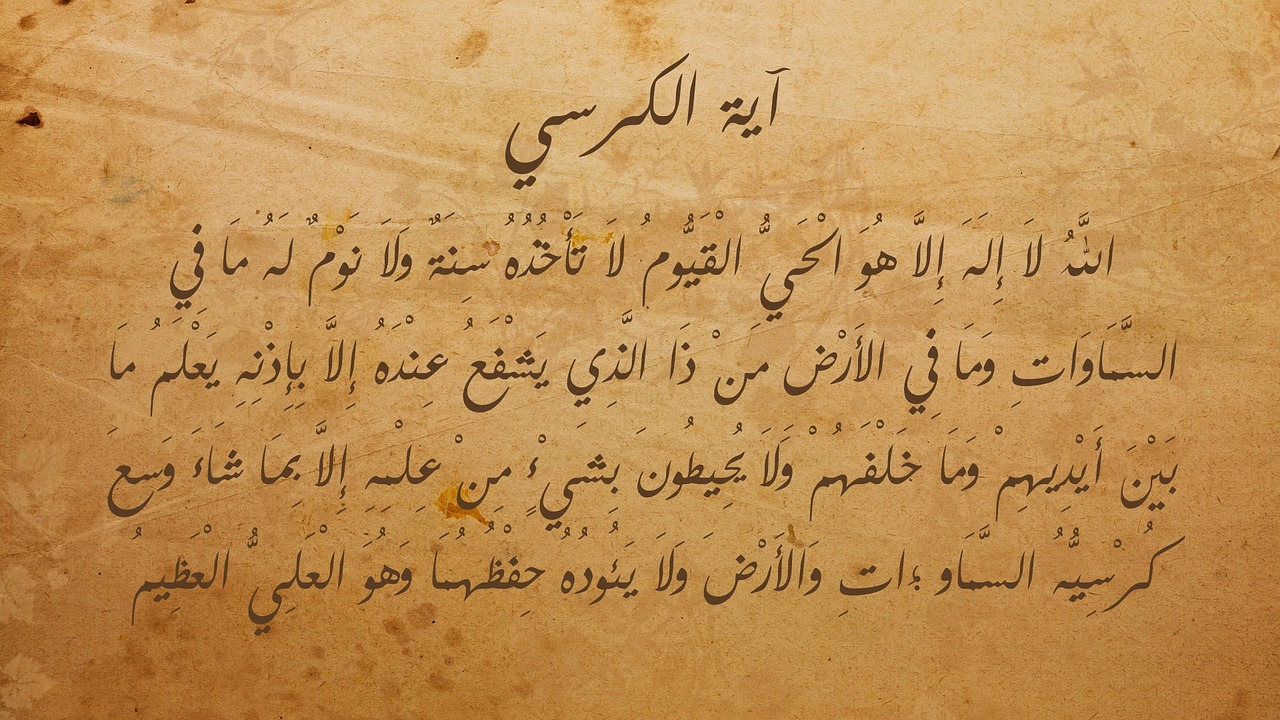

Islamic calligraphy is a sacred art form.

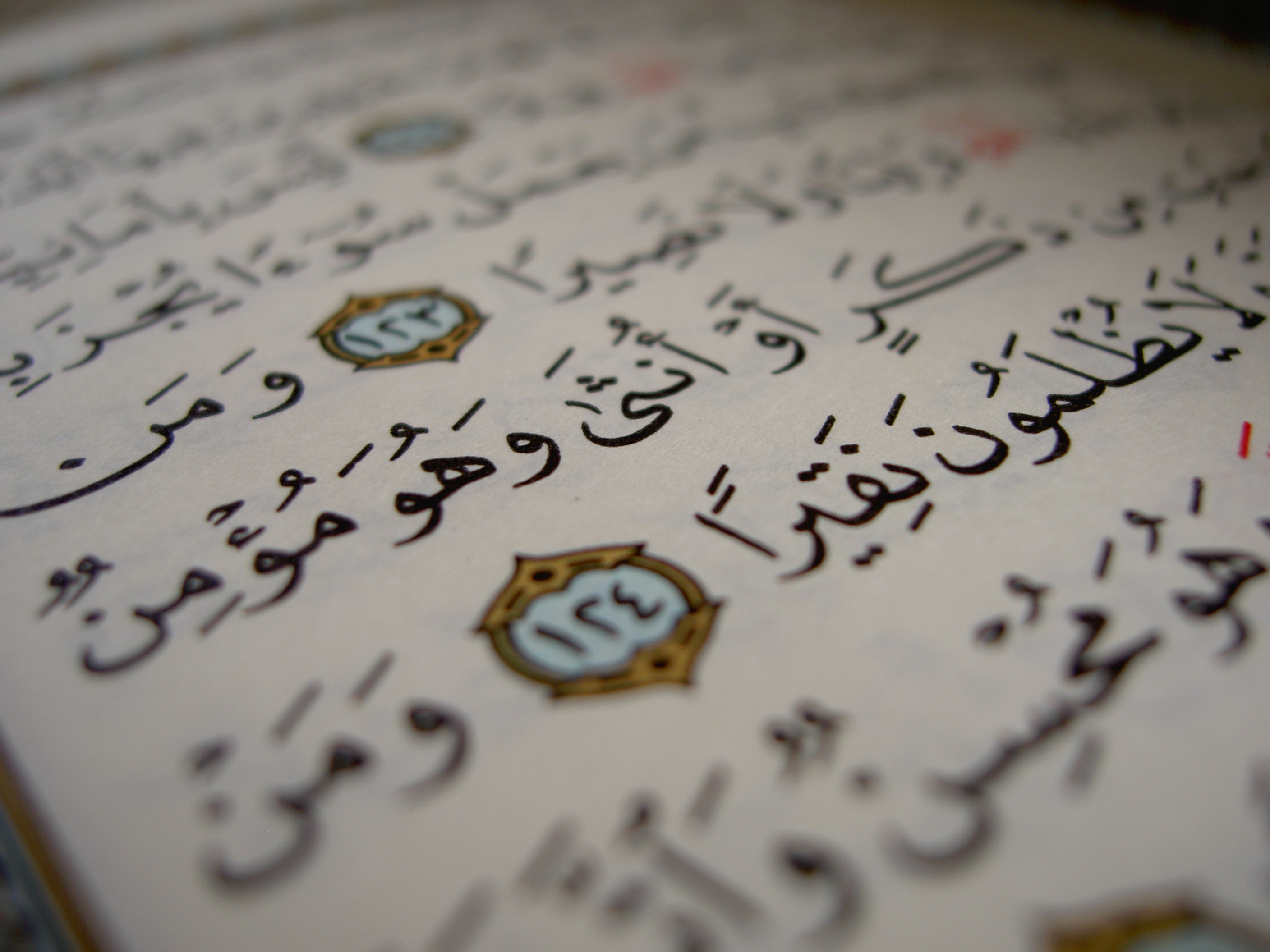

Islamic calligraphy began as the practice of handwriting text directly from, or based on the contents of, the Quran, the sacred book of Islam. Early calligraphers drew inspiration from significant parts of the Quran and particular sayings of the Prophet Muhammad, such as the statement “God is beautiful and loves beauty,” and they took these messages to heart in developing writing styles that would enhance and formalize the text of the Quran as people began to write it down on parchment. Because these artists regarded the words of the Quran as the verbal manifestation of divine truth, they viewed their work as an act of worship. Indeed, experts describe devoted Islamic calligraphers as adopting a meditative and almost mystical approach to penmanship, attempting to craft an inscription that is as pleasing to the eye and as rewarding to the spirit as the harmonious rhythm that emerges from recited verses of the Quran.

Islamic calligraphy exists in a surprising number of places.

While Islamic calligraphy began as the act of inscribing the Quran onto parchment, the art form quickly expanded to other materials. Over the centuries, people have applied calligraphy to ceramics, tile, metal, stone, glass, textiles, carpets, wood, leather, and ivory. In an exhibit of Islamic art, for example, calligraphy exists on almost every precious object, from a carved jewelry box to an inlaid pen case to a decorative water pitcher. But perhaps the most striking place to view Islamic calligraphy is in architecture: Muslim structures all over the world are adorned with beautifully crafted, flowing script running throughout the building. Some of the most famous examples include the Alhambra Palace in Spain, the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, Topkapi Palace in Istanbul, and the Taj Mahal in India.

The instrument that people use to write calligraphy is called a qalam.

The tool that Islamic calligraphers use to create their art is called a qalam. Made from a dried bamboo stem or sometimes a dried reed, the qalam is treated and carved to hold different-colored inks. It’s important to understand, however, that the qalam is much more than just a pen—it is a spiritual tool. In fact, Muslim literature states that the first thing that God created was the qalam, which had the sacred duty to record everything that happened in a person’s life. In addition, because a calligrapher spends so much time using the qalam, it essentially becomes an extension of the hand and a repository for the calligrapher’s ideas and feelings.

For all these reasons, the qalam is treated with a particular reverence, and there’s perhaps no better illustration of this than the ritual of the qalam shavings. According to a custom long respected by calligraphers, all the shavings a calligrapher produces whenever he or she cuts and sharpens his or her qalam must be kept, from the calligrapher’s first day of learning to the day he or she dies. After the death of a calligrapher, the family performs the ritual of collecting the shavings and burning them in the fire that heats the water that will be used to wash the calligrapher’s body. In this way, the calligrapher and his or her qalam both disappear from the material world together.

Image by Doctor Yuri | Flickr

There are a number of different script styles in Islamic calligraphy.

While “Islamic calligraphy” is referred to as a single discipline or art form, there are several different script styles that calligraphers use depending on what they are writing and where they are writing it. For example, the Kufic style, which was popular during the 7th through the 10th centuries, is one of the oldest script forms and the source for other major styles that emerged later, while the Thuluth script style, which developed in the 9th century, was often used for architectural inscriptions because of its larger size and high visibility.